Like every other area of public life, the Corona crisis has hit the German courts with full force and did not leave it unscathed. But the reactions vary: They range from judges and courts still holding ordinary sessions and carrying on with oral hearings to courts being virtually closed except for on-call judges for very urgent matters, with standard civil and commercial matters being postponed ex offico. Three aspects of the current situation are of particular interest:

No suspension of the administration of justice despite a state of emergency ”light”…

A great amount of discussions within the German legal community in the past weeks focused on the question, whether the current Corona crisis created what is referred to as a suspension of the administration of justice (Stillstand der Rechtspflege) in Section 245 German Code of Civil Procedure (ZPO). The provision states that proceedings are interrupted as long as the court ceases its activities as the consequence of war or of any other event. And Section 249 para. 1 ZPO states that an interruption in that sense stops all procedural deadlines; they will recommence in full after the interruption has ended. And as procedural deadlines are of utmost importance in German civil procedure law, an interruption would be a quite convenient way out of the current situation, even leading some presiding judges (Gerichtspräsidenten) indirectly trying to invoke that rule by virtually “closing their court doors”.

Yet, the situation in Germany seems quite far away from a suspension of the administration of justice in that sense. Created in the late 19th century with wars and cholera epidemics in mind, the rule has only been applied in cases after WWII and is commonly interpreted very restrictively to apply only in cases – like war – in which activities of a certain court cease completely and for an indefinite period of time. Despite the very diverse reactions by German courts and judges, today’s situation is far apart from that: Most Courts still do hearings in urgent matters. In addition, even the courts that are virtually closed still retain on-call judges for (very) urgent matters, thus court activity has not ceased completely. Court hearings using videoconference technology are permissible under German law, and have been since 2002 (see Section 128a ZPO), but unfortunately only a very small number of courtrooms are equipped with the necessary technology.

Apart from that, a suspension of the administration of justice would be a nightmare in terms of legal certainty: On the one hand, the suspension of the administration of justice cannot be ordered by a court and then lifted by that same or another court, but comes into effect and ends by automatic operation of law. Therefore, disputes about the exact end of the suspension period and thus the restart of the procedural deadlines would be inevitable; the number of applications for restoration of the status quo ante (Wiedereinsetzung in den vorherigen Stand; Section 233 ZPO) would probably surge. In addition, the legal uncertainty would spill over, so to say, into substantive law: A suspension of the administration of justice would also constitute a case of force majeure (höhere Gewalt) within the meaning of Section 206 German Civil Code (BGB) and therefore would lead to the suspension of limitation periods. Here too, however, the consequences would be anything but clear. Not only would conflicts arise as to the duration of the force majeure, but also as to which location should be taken into account in the case of local or regional differences.

…court publicity coming under pressure from lockdown and curfew regulations…

Another aspect being discussed far and wide in the legal community is the effects of the current curfews (Kontaktsperre) on court publicity, i.e. the right of the general public to attend court hearings. According to Section 169 para. 1 Court Constitution Act (Gerichtsverfassungsgesetz, GVG), hearings before the adjudicating court, including the pronouncement of judgments and rulings, shall be public. Publicity (Öffentlichkeit) in that sense means that everyone must have the opportunity to attend the oral proceedings directly. Yet, the concept of publicity is comprises only the right of the general public to attend the hearings in the courtroom itself – the court files are not public and livestreams from the courtroom are expressly not allowed (Section 169 para. 2 GVG).

Some of the curfews in effect since last weekend – the situation varies from state to state, as curfews are imposed by the German states, not the Federal Government – make it illegal to leave home, except for an important reason. An important reason according to those curfew regulations are “urgent matters in courts”. That had triggered a discussion in the German legal community whether visiting a court hearing simply to attend it and to constitute publicity is an “mportant reason. And even if it is: Is the chilling effect of these regulations – would anybody really want to discuss these questions and its constitutional implications with controlling police officers? – itself a restriction on publicity? These questions remain unanswered for now. But as publicity can be excluded by the court for health reasons of participants (e.g. in mafia cases), a curfew imposes for health reasons will probably not be deemed a violation of publicity, if the hearings in question are very urgent and cannot be adjournment to a time of publicity.

And by the way: For the judges and the lawyers to enter into a “gentlemen’s agreement” to perform a hearing without publicity is impossible – or least highly risky – under German law. In case of an appeal, that decision would probably be overturned, the parties’ consent notwithstanding. For according to the German understanding, publicity serves not so much to protect the individual parties as to control the exercise of state power, to strengthen the independence of the judiciary and to protect the public’s trust in it. Publicity therefore is withdrawn from parties’ disposition: According to Section 547 No. 5 ZPO a violation of the concept of publicity is an absolute ground for an appeal on points of law (Revision).

..and a silent legislator

What strikes most, given that these issues were widely discussed, is that the specific legislation to alleviate the effects of the Corona” enacted yesterday does not address any of these problems. That is especially remarkable, as a solution has already been proposed by chancellor Merkel’s parliamentary group: A re-enactment of the concept of court holidays (Gerichtsferien) that was abolished in 1996. Reintroducing temporary court holidays would interrupt most procedural deadlines and would reduce hearings to urgent matters. Hence, the legislation would have provides courts and parties with much-needed clarity and legal certainty and an identical procedural reaction to the Corona crisis nationwide instead of a piecemeal approach. The legislation did address similar issues in criminal proceedings, but left ZPO and GVG unchanged.

This is a guest post by Benedikt Windau, the founder of zpoblog.de. Benedikt has covered the impact of Corona on German litigation in several posts on his blog (see here), on lto.de and FAZ Einspruch – for those of you who read German, these are highly recommended, as is zpoblog in general.

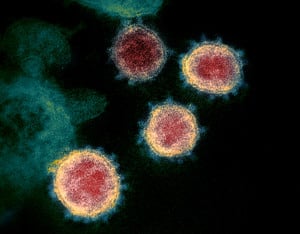

Photo: NIAID Rocky Mountain Laboratories (RML), U.S. NIH, SARS-CoV-2 49534865371, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons